Long time readers of this blog may recall some posts that highlighted issues with the way gradings are conducted. Notably, that they are an opinion poll of judges, and that there are no genuine measures to determine what level someone is training at. This post is going to introduce a new system for grading that resolves this issue.

The Problem

It’s possible that some sensei do have very specific grading criteria. If they do though, they’re either kept by the individual, or not used at an organisational level. Thanks to the internet, it is possible to find the grading syllabi for many aikido organisations. It’s also possible to find the criteria for passing a grading in an organisation.

All of these grading criteria have a similar problem. None of them specify what they mean. People will argue that they do, but they really don’t. What they actually say is something like, “Demonstrates technique at a level appropriate to X” where X is the grade. That’s not specific, that’s asking for an opinion on a student’s level of ability. This is also style independent. Every single grading syllabus I’ve seen follows this pattern.

If an organisation consists of a single club, or the same person awards all grades, then this isn’t a problem. That is not the majority of organisations though.

A Way To Solve It

There is a very simple and obvious way to fix this. Get specific with the criteria. When you do that, it no longer asks for an opinion of the examiner. The student either did the thing or they did not. It reduces to observation of what actually took place. This is beneficial as it not only removes opinion, it also helps to eliminate any bias an examiner may have.

How Do We Get Specific Though?

I am very fortunate to know several university lecturers. I reached out to them and asked a simple question. “When a student submits something for examination, and there is more than one mark available, how do you determine how many marks to award?”

Reassuringly, they all came back with the same answer. They introduced me to a marking rubric, and briefly explained how it worked. Having never had to mark anything in my life this was a new concept, but it would provide the solution I was seeking.

A marking rubric essentially states criteria to define different levels of competence in the area examined. Marks are awarded based on the criteria met. It’s a very simple concept, but as I soon learned, much harder to implement.

The Proposed Solution

With the concept of a rubric in mind, a solution came together. Building on the idea of using a scorecard, I now had a method to create one. A set of examination rules would have to go along with this, but that would be the easy part.

The basic idea was to create a scorecard for aikido gradings, a set of rules to apply to the scoring, and determine specific criteria for each technique. Students would need to meet a minimum score to pass the grading. It would become like any other standard exam.

Since grading syllabi become more advanced as students progress, each grade would build upon the previous one. This allows for criteria to become more stringent and more things to examine for. Additionally, the pass mark would rise, and more techniques would appear. None of this is too different from the way most aikido gradings are conducted. The difference here is that there would be highly specific criteria to judge against.

The Outcome

The first thing to note is that this is specific to what I think a student should be capable of doing to pass a grading. A second observation is that I believe a student should just scratch into a grade and then grow through it. I’m also not a fan of failing kyu grades. I’ve done it, but am never happy about it.

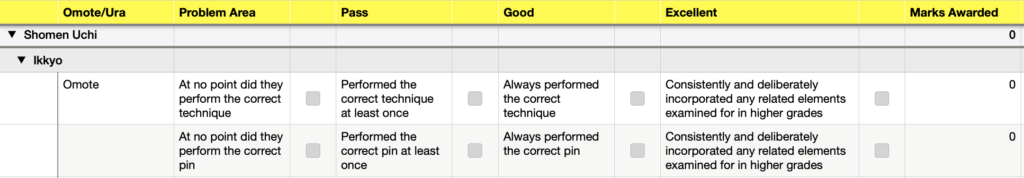

On the rubric, a box is checked depending on what level of criteria they reach. Each of the criteria are mutually exclusive, and award different points. A Problem Area scores 0, a Pass 1, a Good 2, and an Excellent 3.

5th Kyu To 1st Kyu

To demonstrate what this looks like in practice, we’ll take a look at shomen uchi ikkyo omote from 5th kyu through to 1st kyu.

As you can see, the requirements for 5th kyu are very simple. Necessarily so, because at this point they’ve only been training for a few weeks. It does provide a very simple starting point to build from though, both for the student and the instructor. Frankly, if they can’t achieve this, they should not be grading.

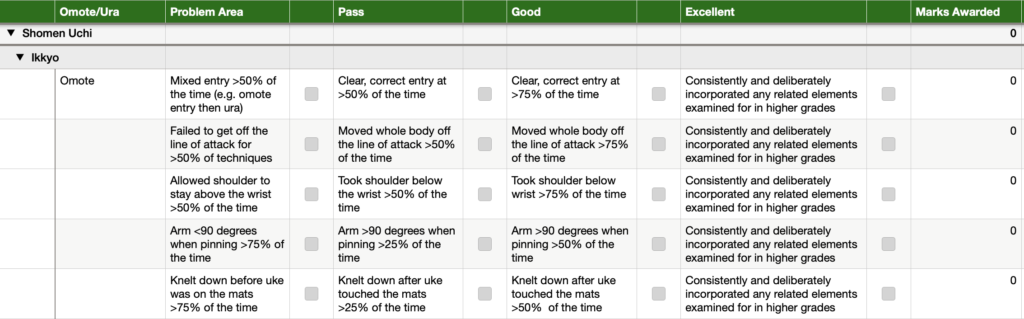

4th Kyu

The easiest test is over, and the student has some commitment to their training. As such, the criteria start to get more specific. Gone is the simplicity of ‘did they do the right thing?’ Now, it’s looking at how much of the right thing they did.

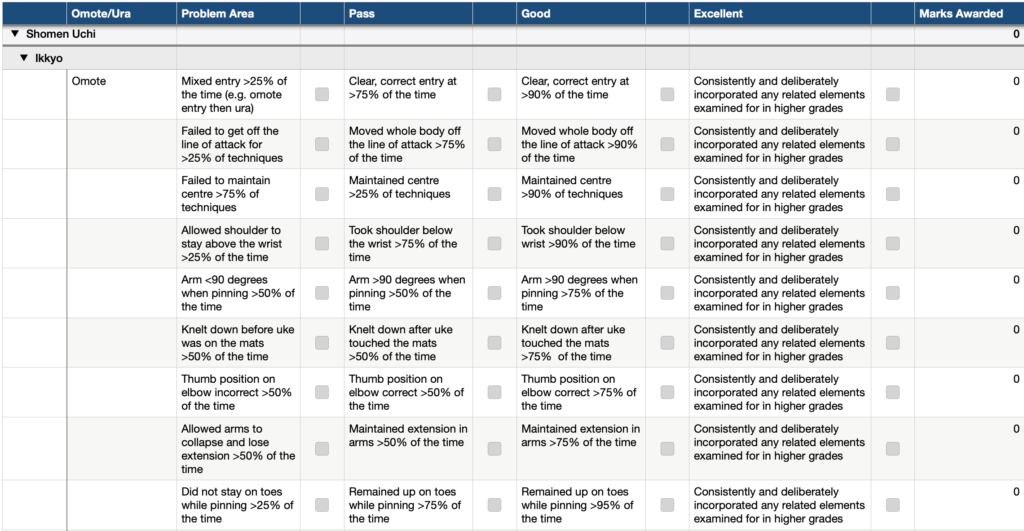

3rd Kyu

Compare these criteria with the 4th kyu ones, you’ll notice that the percentages get higher as we progress through the grades. In general, when adding new criteria it allows for a high failure rate. If a criteria carries through, then the acceptable failure rate drops.

2nd Kyu

At this stage, it starts to get a lot tougher for the student. Still not anything they should have difficulty with if they are at that level.

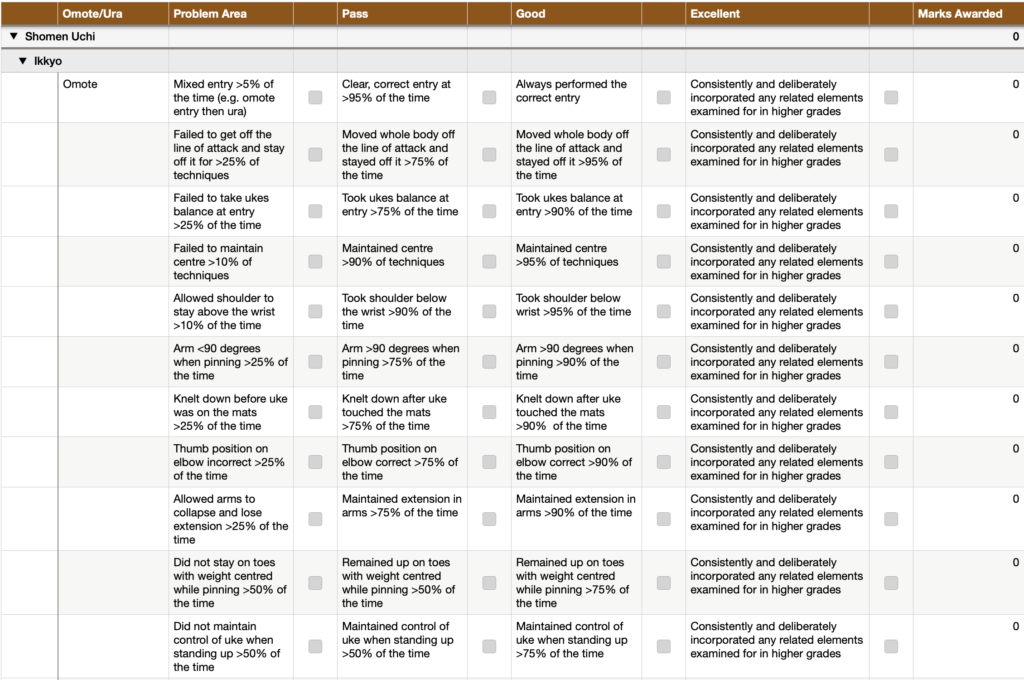

1st Kyu

By the time they reach 1st kyu, the earliest criteria are very unforgiving. This encourages a focus on the fundamentals the whole way through training.

Problems When Creating

There were some issues when creating these rubrics.

The first is that it became difficult to maintain consistency through the grades. The simplest thing to do was copy and paste the previous grade, then alter it. Without some careful thought though, percentages for passing quickly became out of sync. This was particularly true when adding in the same technique, but from a different attack.

A second problem was the sheer length of time it takes. I cannot be precise because I honestly do not know. What I can say though is it has taken at least 50 hours so far, probably a lot more. It’s the cumulative nature that causes this. For the 5th kyu syllabus, there are a total of 90 rows in the spreadsheet. That covers all the techniques for our organisation. In contrast, the 1st kyu syllabus has 1,765 rows. As each rubric builds and adds new criteria and techniques, it keeps getting bigger. At this stage I suspect the sandan criteria will reach somewhere around 2,500 rows.

But Does It Work?

Happily, yes, it does. The last two aikido gradings I conducted used this system. The scorecards proved enormously useful, and highlighted certain alterations I should make.

The biggest lesson is that they work best in a formal grading. This is not something I usually do. I prefer to run a normal training session, but teach very little. The techniques practiced are all from the grading syllabus. I find that running an aikido grading this way takes much of the pressure off the students. Unfortunately, when using a scorecard, this makes it hard to match the correct criteria. Some thought around this will have to take place before the next grading.

I could solve this problem by reducing the number of criteria for each technique, but that would defeat the entire purpose.

Some Benefits

There have been several tangible benefits from this exercise. I consider these to be equally important, so they are not in any special order.

To do this, you have to understand on a fundamental level what you want to see for each grade. The process forces you to consider each technique and grade in a way most people never think about. You begin to understand what you think is an acceptable level to pass a grading. You cannot get away with saying, ‘a level appropriate to X’. This process forces a definition from you.

When using this system, it highlights similar failings and successes across the range of techniques. Looking at the scorecard uncovers aspects that might have gone unnoticed. It allows you to look at each student’s problem areas. The examiner can now pick out groupings across the entire range, rather than just individual techniques. Even better, you can pick them up across students.

This is beneficial as it highlights gaps in the teaching style. When reviewing the grading scorecards you may see that every student has difficulty with the same thing across multiple techniques. If so, that’s a teaching failure, not a student issue.

Some things are student related though, and the rubric will highlight when those are related to an individual student. The result is the basis of a personal training plan for each student that grades. Both student and sensei discover what areas they are weak in, and can focus to make those better as they progress through the grade.

Would Recommend

Creating this rubric has been an incredible amount of work, far more than I would have thought when I started. I began this in May 2020, have been working at it since then, and am still not finished.. There have been large gaps concentrating on other aspects, but still, it takes time. Regardless, it is has been an incredibly valuable exercise with notable benefits:

- A better understanding of each grade level

- An ability to develop a personal training plan for every student

- Highlighting gaps in what I teach

- Removal of bias from grades awarded

- A record of how a student has performed if they change dojo

- The beginnings of grade standardisation for aikido gradings that I conduct

Despite the work required, I would recommend that each sensei does this. The benefits outweigh the time cost, and it can help bring much needed standardisation to aikido gradings.

If you can afford it, and would like to help out,

consider donating some brain fuel!

Also, if you enjoyed this post you can find further insights in this book.

Good article. In addition, having another dojo test, your students would be better. A non-bias instructor can give feedback specifically for the student to improve for the next test and also give a solid pass or a mediocre pass to show how much the student needs to improve.

In addition, I would recommend the test consisting of all the previous techniques plus new ones. That way the student is expected to improve on their skills from test to test. For black belt testing there should be many instructors that give feedback individually in a written form, and their certificate should come with all the feedback.